My insanely ambitious simulation game.

Sept 19, 2016 15:34:28 GMT

Moopli, Skyguy98, and 2 more like this

Post by Mouthwash on Sept 19, 2016 15:34:28 GMT

It's probably more ambitious than Thrive. I believe that human politics can be simulated completely in a 3D setting, with a real, emergent civilization built from the ground up by individuals. There would be a set population of humans in a generated world (as many as any computer could handle). Gameplay is divided between ‘God mode’ and control of a single person, which you are able to switch between at any point.

Individuals

There are five elements to every human being:

1. Physical state

Their diseases, injuries or scars, need for air or nourishment, level of exhaustion, strength and muscle mass, etc. If they are 6'2 or they have a harelip or are circumcised, it gets shown here. Simple genetic algorithms determine some things like appearance.

2. Mental state

Their primary mental state. Think of something along these lines:

The eight emotions (fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, anticipation, joy, trust) are given straightforward triggers and bordering emotions can exist concurrently, as shown, to produce the higher emotions.

There would also be more normal, static personality traits like “patient” or “ambitious,” but that's not something I need to plan here.

3. Outlook

Their fundamental value. This decides the beliefs that they hold, how they respond to situations, what goals they have, and how they lean in the social scale. For example, someone who values material growth would seek the freedom to profit in their station, and reject patriarchal or communal ideas. Someone who values survival would consider only their own needs or those of their immediate family. Someone who seeks knowledge or meaning would probably join a cult or become a philosopher, and would tend to favor broad theories over practical ideas. Etc.

Emotional and physical triggers are the determining factor in outlook (a person who lives in constant fear for their life will value survival, but that gets less common the more peaceful and wealthy the society they live in). Outlooks can change in periods of transition or stress.

4. Ideas

Basically a tech tree. Every person has ideas; these are what constitute their knowledge. Furthermore, while certain ideas may have prerequisites to be invented, these may not apply to the idea being taught to one person by another. The average person’s ideas will shift over time as their society advances, and they may cease to learn earlier ones even if their own ideas were derived from them; most real-life people would not be able to rebuild a modern society from scratch even if they could fix computers or drive a truck.

Each idea has four levels of knowledge, with varying rules for transmission:

Level zero: This is knowing that the idea exists, but not knowing what it is. If primitive spearmen are fired at by cannon, they're likely to associate it with danger and noise, but they won't actually realize it works by exploding powder launching a projectile. This produces awe or fear, depending on the circumstance.

Level one: Having a basic understanding of an idea. Shouldn’t be too much use in most cases.

Level two: Being educated with an idea. Such a person, for instance, could grow corn and fix a broken staircase, but would not be able to maximize their crop yield or to build a staircase themselves.

Level three: Understanding an idea completely. These people could teach their ideas to others far more efficiently than level two, and almost all innovation would require this level.

How to invent an idea? If a person knows the prerequisite idea(s), than engaging in certain actions accumulate "points" which give a chance of inventing that idea. These actions need not be deliberate. A mathematician may sit down and systemically work out geometry, or an officer can think of a brilliant new tactic after being repulsed by the enemy. For most ideas the actions required are rather complex. To take our example of an officer inventing a tactic:

12 points from time spent skirmishing in battle

20 points from time spent studying skirmishing tactics

7 points from time spent giving orders

3 points from time spent socially interacting with soldiers

38 points because men under his influence killed others with javelins

20 points because men under his influence were killed by javelins

45 points from time spent training men with javelins

-74 points from time spent doing miscellaneous things

=

71

multiplied by a 1.20% bonus for his outlook/traits = 85.2

85.2 translates into a 8.52% chance of getting [insert throwing tactic idea here] this month.

That’s an extremely rough concept; the conditions could be made into anything imaginable. The officer still needs quite a bit of luck to actually invent the idea, since these modifiers only last the month, although I suppose there ought to be a small, permanent bonus for accumulating enough points.

Certain ideas have opposing counterparts. A person may ‘believe’ one idea over another competing idea. The outlook of a person decides which of them he takes as a belief.

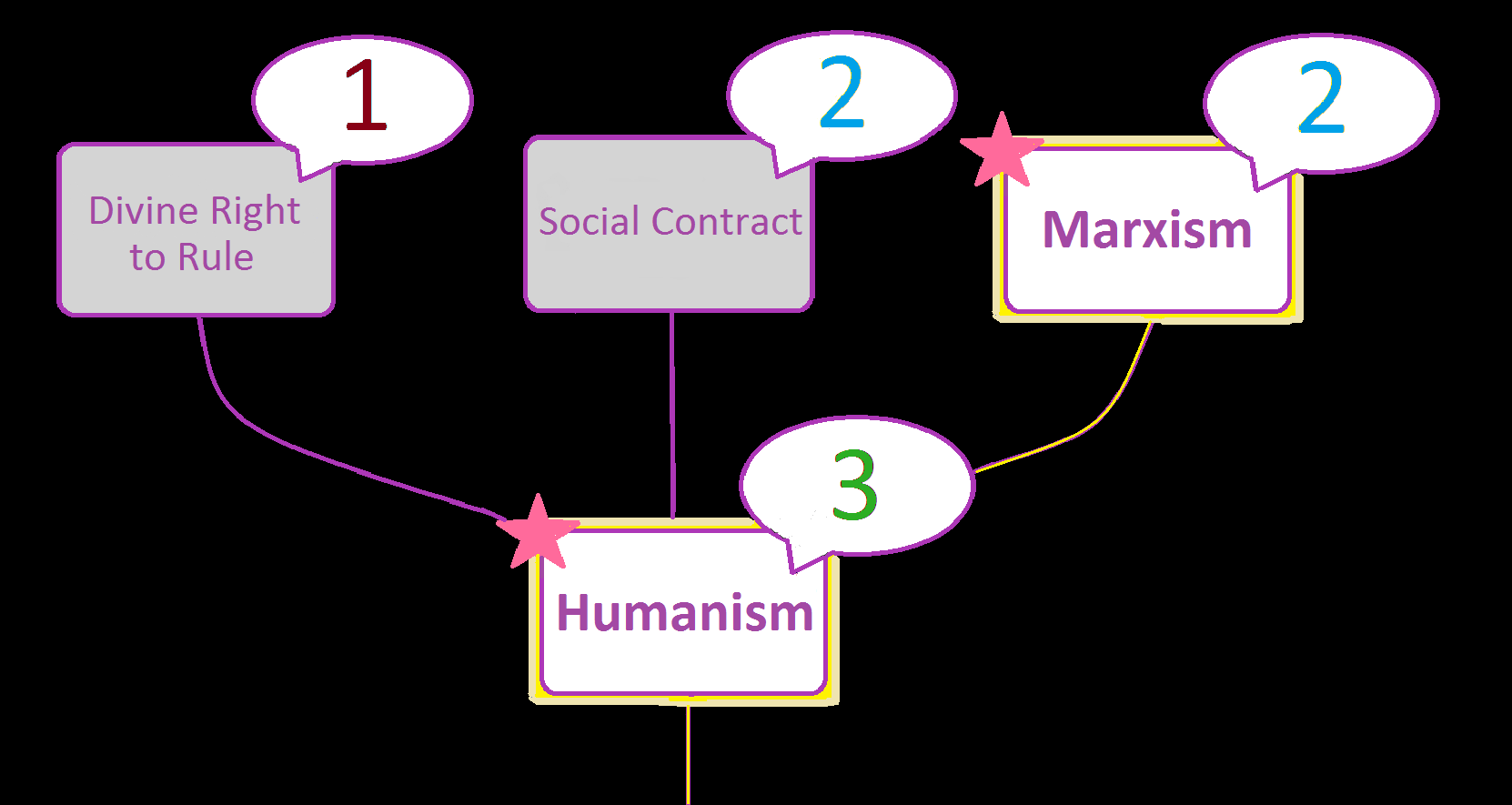

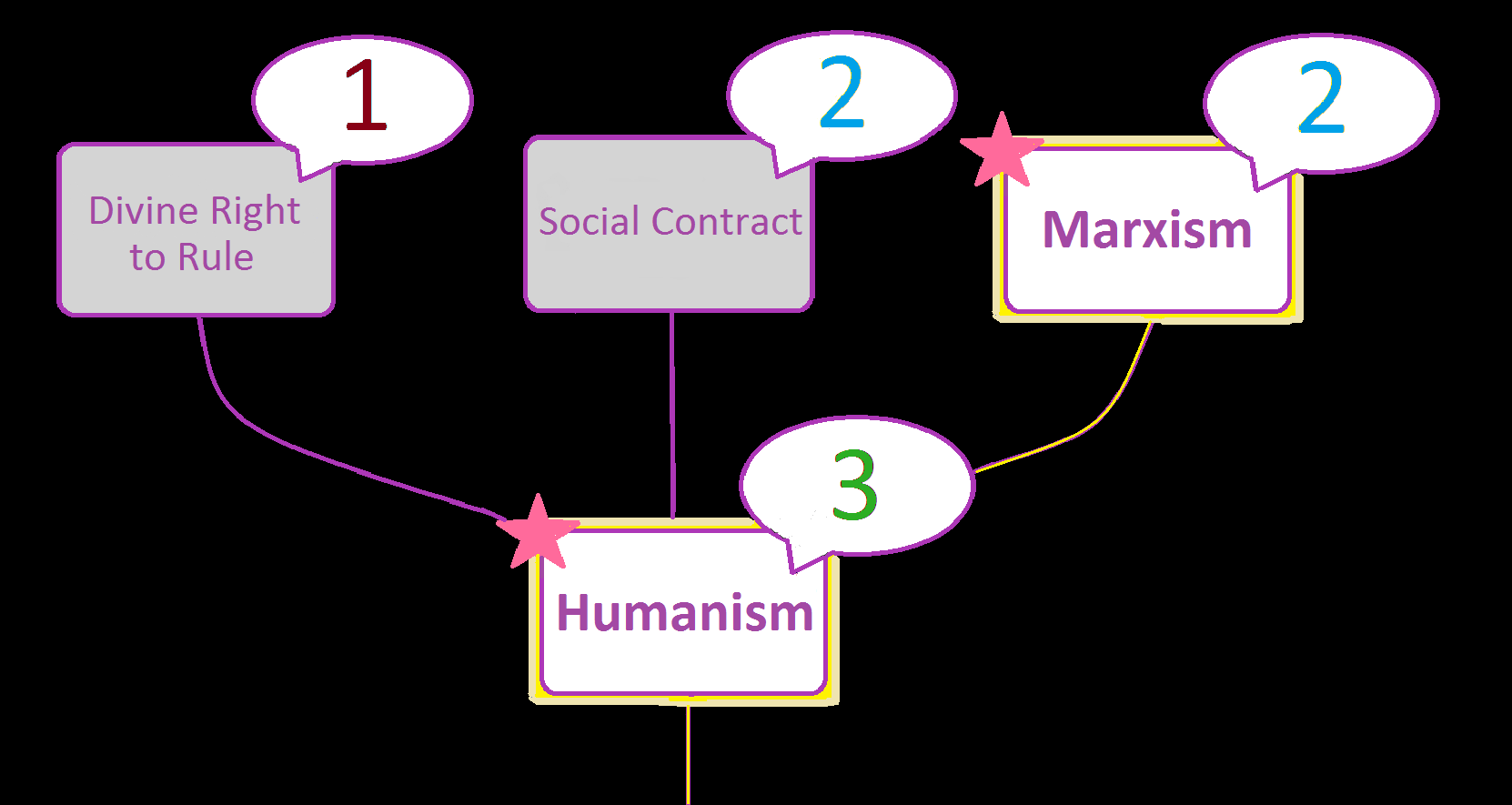

Some concept art, with the numbers corresponding to levels of knowledge (I made it a year ago, and yes, I know that humanism is an odd choice to lead to divine right or Marxism; they're placeholders):

As seen here, the person fully comprehends the idea of humanism (or whatever equivalent you want to imagine) and has studied its various offshoot ideas. He accepts Marxism, which requires him to accept its parent ideas as well.

Sometimes beliefs develop that support each other mutually, and are transferred more or less wholesale between humans. These are doctrines. They mean that ideas which aren't really dependent on each other can occasionally be intertwined. For creating a doctrine, just imagine this something like this based off of ideas.

5. Awareness

A person's awareness of the physical world. As well as keeping track of active objects (such as other people, animals, storms, etc.) this takes the form of a 'map' for each person. Information is gathered about the world either through viewing it or through interacting with others. However, physical maps (which would require cartography-related ideas) are very important, since the maps in people's heads degrade if not constantly refreshed.

Macro-Politics

There are four main components which make up the 'macro' gameplay:

1. Societies

This game will attempt to emulate a social consciousness. Any person that is aware of another person has an attitude towards them. Actual interaction between people is not necessary for this; for instance, a king’s visage on a coin is enough to create an attitude towards him among his subjects. It is communication that creates societies, not anything abstract like 'culture' or 'religion.'

2. Groups

These are formed in societies that grow past a single extended family (they become better organized the longer they last). Their function is determined by consensus of their members and can be altered according to those members' priorities. They encompass everything from an warband to a school to a ruling aristocracy. Each one has its own wealth, whether by patronage or by their members' pockets, and they attract like-minded individuals through notoriety. However, the motives of their individual constituents will still exist; if the group's aims don’t remain cohesive it will fall into corruption, or dissolve outright.

3. Power gradients

This is how much physical power any person has. You could call it a kind of 'sphere of influence.' The offensive value depends on what sort of damage a person can do: size and strength boosts it, but not as much as having a weapon. Any individual’s power gradient extends across the whole of the map, but peters off exponentially in areas outside of their immediate location, depending on their ability to travel. Not many people will fight if they are under the influence of a larger power gradient; hence, this allows an organized group of soldiers can dominate a much larger population.

It is important to note that the values of gradients are entirely in the heads of people. A row of spearmen in formation, for instance, see charging horsemen as having a lower value than some scattered swordsmen would. Those same spearmen, not knowing of gunpowder, would assign a row of riflemen a very low score until they started firing. Scores can change even on an individual basis. A warrior that kills five others, or a line of chariots that smashes an enemy's formation will be assigned higher scores by their opponents than they normally would. I can imagine a very skilled general winning victories and gaining lots of momentum from this. As well as individual soldiers or armies, this boost can permanently alter how certain types of weapons are seen by an entire society, serving as an all-purpose corrective to the game's balance.

Applying a power gradient to groups or armies will be some combination of a single score, the scores of its various subgroups, and all its individuals. It's not something I can answer without actually making the game myself.

4. Laws

Groups create and enforce certain rules upon themselves and those they have influence over. This is a very non-emergent aspect of the game, with certain actions being canned and made contingent on ideas (property, customs, status, etc). They are still triggered through emergent pressures, though.

Individuals

There are five elements to every human being:

1. Physical state

Their diseases, injuries or scars, need for air or nourishment, level of exhaustion, strength and muscle mass, etc. If they are 6'2 or they have a harelip or are circumcised, it gets shown here. Simple genetic algorithms determine some things like appearance.

2. Mental state

Their primary mental state. Think of something along these lines:

The eight emotions (fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, anticipation, joy, trust) are given straightforward triggers and bordering emotions can exist concurrently, as shown, to produce the higher emotions.

There would also be more normal, static personality traits like “patient” or “ambitious,” but that's not something I need to plan here.

3. Outlook

Their fundamental value. This decides the beliefs that they hold, how they respond to situations, what goals they have, and how they lean in the social scale. For example, someone who values material growth would seek the freedom to profit in their station, and reject patriarchal or communal ideas. Someone who values survival would consider only their own needs or those of their immediate family. Someone who seeks knowledge or meaning would probably join a cult or become a philosopher, and would tend to favor broad theories over practical ideas. Etc.

Emotional and physical triggers are the determining factor in outlook (a person who lives in constant fear for their life will value survival, but that gets less common the more peaceful and wealthy the society they live in). Outlooks can change in periods of transition or stress.

4. Ideas

Basically a tech tree. Every person has ideas; these are what constitute their knowledge. Furthermore, while certain ideas may have prerequisites to be invented, these may not apply to the idea being taught to one person by another. The average person’s ideas will shift over time as their society advances, and they may cease to learn earlier ones even if their own ideas were derived from them; most real-life people would not be able to rebuild a modern society from scratch even if they could fix computers or drive a truck.

Each idea has four levels of knowledge, with varying rules for transmission:

Level zero: This is knowing that the idea exists, but not knowing what it is. If primitive spearmen are fired at by cannon, they're likely to associate it with danger and noise, but they won't actually realize it works by exploding powder launching a projectile. This produces awe or fear, depending on the circumstance.

Level one: Having a basic understanding of an idea. Shouldn’t be too much use in most cases.

Level two: Being educated with an idea. Such a person, for instance, could grow corn and fix a broken staircase, but would not be able to maximize their crop yield or to build a staircase themselves.

Level three: Understanding an idea completely. These people could teach their ideas to others far more efficiently than level two, and almost all innovation would require this level.

How to invent an idea? If a person knows the prerequisite idea(s), than engaging in certain actions accumulate "points" which give a chance of inventing that idea. These actions need not be deliberate. A mathematician may sit down and systemically work out geometry, or an officer can think of a brilliant new tactic after being repulsed by the enemy. For most ideas the actions required are rather complex. To take our example of an officer inventing a tactic:

12 points from time spent skirmishing in battle

20 points from time spent studying skirmishing tactics

7 points from time spent giving orders

3 points from time spent socially interacting with soldiers

38 points because men under his influence killed others with javelins

20 points because men under his influence were killed by javelins

45 points from time spent training men with javelins

-74 points from time spent doing miscellaneous things

=

71

multiplied by a 1.20% bonus for his outlook/traits = 85.2

85.2 translates into a 8.52% chance of getting [insert throwing tactic idea here] this month.

That’s an extremely rough concept; the conditions could be made into anything imaginable. The officer still needs quite a bit of luck to actually invent the idea, since these modifiers only last the month, although I suppose there ought to be a small, permanent bonus for accumulating enough points.

Certain ideas have opposing counterparts. A person may ‘believe’ one idea over another competing idea. The outlook of a person decides which of them he takes as a belief.

Some concept art, with the numbers corresponding to levels of knowledge (I made it a year ago, and yes, I know that humanism is an odd choice to lead to divine right or Marxism; they're placeholders):

As seen here, the person fully comprehends the idea of humanism (or whatever equivalent you want to imagine) and has studied its various offshoot ideas. He accepts Marxism, which requires him to accept its parent ideas as well.

Sometimes beliefs develop that support each other mutually, and are transferred more or less wholesale between humans. These are doctrines. They mean that ideas which aren't really dependent on each other can occasionally be intertwined. For creating a doctrine, just imagine this something like this based off of ideas.

5. Awareness

A person's awareness of the physical world. As well as keeping track of active objects (such as other people, animals, storms, etc.) this takes the form of a 'map' for each person. Information is gathered about the world either through viewing it or through interacting with others. However, physical maps (which would require cartography-related ideas) are very important, since the maps in people's heads degrade if not constantly refreshed.

Macro-Politics

There are four main components which make up the 'macro' gameplay:

1. Societies

This game will attempt to emulate a social consciousness. Any person that is aware of another person has an attitude towards them. Actual interaction between people is not necessary for this; for instance, a king’s visage on a coin is enough to create an attitude towards him among his subjects. It is communication that creates societies, not anything abstract like 'culture' or 'religion.'

2. Groups

These are formed in societies that grow past a single extended family (they become better organized the longer they last). Their function is determined by consensus of their members and can be altered according to those members' priorities. They encompass everything from an warband to a school to a ruling aristocracy. Each one has its own wealth, whether by patronage or by their members' pockets, and they attract like-minded individuals through notoriety. However, the motives of their individual constituents will still exist; if the group's aims don’t remain cohesive it will fall into corruption, or dissolve outright.

3. Power gradients

This is how much physical power any person has. You could call it a kind of 'sphere of influence.' The offensive value depends on what sort of damage a person can do: size and strength boosts it, but not as much as having a weapon. Any individual’s power gradient extends across the whole of the map, but peters off exponentially in areas outside of their immediate location, depending on their ability to travel. Not many people will fight if they are under the influence of a larger power gradient; hence, this allows an organized group of soldiers can dominate a much larger population.

It is important to note that the values of gradients are entirely in the heads of people. A row of spearmen in formation, for instance, see charging horsemen as having a lower value than some scattered swordsmen would. Those same spearmen, not knowing of gunpowder, would assign a row of riflemen a very low score until they started firing. Scores can change even on an individual basis. A warrior that kills five others, or a line of chariots that smashes an enemy's formation will be assigned higher scores by their opponents than they normally would. I can imagine a very skilled general winning victories and gaining lots of momentum from this. As well as individual soldiers or armies, this boost can permanently alter how certain types of weapons are seen by an entire society, serving as an all-purpose corrective to the game's balance.

Applying a power gradient to groups or armies will be some combination of a single score, the scores of its various subgroups, and all its individuals. It's not something I can answer without actually making the game myself.

4. Laws

Groups create and enforce certain rules upon themselves and those they have influence over. This is a very non-emergent aspect of the game, with certain actions being canned and made contingent on ideas (property, customs, status, etc). They are still triggered through emergent pressures, though.